How to Use Locals Frequently Asked Questions and Help Topics:

https://support.locals.com/en/article/how-do-i-upload-videos-podcasts-photos-r49es4/

If you need more help contact LOCALS Support at:

He was ordered to abandon his friends at the Alamo and ride through enemy lines with their final message. He obeyed—and spent the rest of his life carrying the guilt of surviving.

February 1836. The Alamo mission in San Antonio was surrounded by thousands of Mexican troops under General Santa Anna. Inside, roughly 200 Texian and Tejano defenders knew they were probably going to die.

Captain Juan Seguín knew it too.

He was thirty years old, a Tejano rancher who'd joined the Texas Revolution despite being ethnically Mexican. His father had fought for Mexican independence; now Juan was fighting against the Mexican government for Texas independence.

It was complicated. And about to get worse.

Commander William B. Travis gathered his officers. The situation was desperate—no reinforcements were coming, supplies were dwindling, Santa Anna's artillery was pounding the walls.

Travis needed someone to carry messages through enemy lines to General Sam Houston. Someone who could navigate the Texas countryside, who spoke Spanish fluently, who might pass as a Mexican soldier if stopped.

Travis looked at Juan Seguín.

"You're the only one who can make it through," Travis said. Not a request. An order.

Seguín protested. His men—the Tejano defenders he commanded—were staying to fight. How could he abandon them? How could he leave his friends James Bowie, Davy Crockett, and the others to die while he rode away?

Travis was firm. "If you stay, your death changes nothing. If you leave, you might save Texas."

The logic was sound. The guilt was unbearable.

Before dawn on February 25, 1836, Juan Seguín mounted his horse. The Alamo's walls were still standing. His friends were still alive. He turned once more toward the fortress—lit by cannon fire, defiant against impossible odds.

Then he rode into the darkness.

The journey was a nightmare. Mexican patrols were everywhere. Seguín traveled at night, hid during the day, avoided roads, slept in arroyos and behind rocks.

Every sound behind him could be death. Every rider on the horizon could be the patrol that would capture and execute him as a traitor.

He pushed his horse to exhaustion. Changed direction constantly. Went days without sleep, fueled by duty and dread.

When he finally reached Sam Houston's camp near Gonzales, Seguín delivered Travis's message: the Alamo was surrounded, reinforcements were desperately needed, the defenders would fight to the last man but couldn't hold forever.

Houston listened in grim silence. He knew what Seguín didn't want to say: by the time any help arrived, it would be too late.

On March 6, 1836—nine days after Seguín rode out—the Alamo fell.

Santa Anna's troops overwhelmed the walls in a pre-dawn assault. Every defender died fighting. Travis, Bowie, Crockett—all the men Seguín had left behind—were killed.

When news reached Houston's camp, Seguín was devastated. He'd obeyed orders, completed his mission, done everything right.

And all his friends were dead.

The guilt was crushing. Why had he survived when they hadn't? Why had Travis chosen him to leave?

But there was no time for grief. Houston was retreating east, trying to avoid Santa Anna's much larger army while building Texas forces. Seguín buried his guilt and kept fighting.

On April 21, 1836, at San Jacinto, Houston finally turned and attacked. The battle lasted eighteen minutes—a surprise assault that caught Santa Anna's army during siesta.

Juan Seguín commanded the only Tejano unit in Houston's army. His men fought with fury born from personal loss—many had family who'd died at the Alamo or Goliad.

Texas won decisively. Santa Anna was captured. Texas independence was secured.

Seguín had helped win the war. But victory felt hollow.

After the revolution, Seguín was elected to the Texas Senate. He became mayor of San Antonio. He worked tirelessly for reconciliation between Anglos and Tejanos, trying to build a Texas where everyone who'd fought for independence would be welcome.

Instead, he watched anti-Mexican sentiment grow toxic.

Anglo settlers arriving after the war didn't care that Tejanos like Seguín had fought for Texas. They saw Spanish surnames and heard Spanish language and wanted them gone.

Seguín received death threats. His property was targeted. Former allies turned against him simply because he was ethnically Mexican—never mind that he'd nearly died carrying messages from the Alamo, never mind that he'd fought at San Jacinto.

In 1842, facing violence from the people he'd helped liberate, Juan Seguín fled to Mexico.

Think about that. A hero of the Texas Revolution, forced to leave Texas because Texians decided Mexicans weren't real Texans.

He lived in Mexico for years, even served briefly in the Mexican army—which Texas used as "proof" he'd been a traitor all along, conveniently forgetting his actual service.

Seguín eventually returned to Texas in the 1850s, living quietly until his death in 1890 at age eighty-four.

For decades, his story was forgotten or distorted. Anglo-centric versions of Texas history emphasized Travis, Bowie, and Crockett while erasing or minimizing Tejano contributions.

It's only recently that historians have fully recognized what Juan Seguín sacrificed.

He left the Alamo carrying his friends' final messages, knowing he'd be called a coward or traitor by people who didn't understand.

He fought at San Jacinto and helped win Texas independence.

He worked for years trying to build an inclusive Texas that honored all its defenders.

And he was driven out by the very people he'd fought to liberate—because they couldn't see past his Mexican heritage to recognize his Texas loyalty.

Today, the city of Seguin, Texas, is named after him. Historians recognize him as one of the Texas Revolution's most important—and most tragic—figures.

But his story asks uncomfortable questions Texas still struggles with: Who gets to be a "real Texan"? Does ethnicity matter more than sacrifice? Can you fight for a place that doesn't want you?

Juan Seguín rode out of the Alamo at dawn, burdened with messages from men about to die.

He spent the rest of his life carrying something heavier: survivor's guilt, and the knowledge that the Texas he'd fought for didn't want him in it.

History remembers the Alamo's defenders as heroes who died for freedom.

It should also remember the man who survived—who carried their final words through enemy lines, who fought at San Jacinto, who tried to build the Texas they'd died for.

And who was eventually forced to leave it.

Food for thought y'all!

The BAD APPLE EFFECT 🍎

I'm seeing more and more people that fall victim to this phenomenon. One negative reaction attracts others to it like a magnet. One that's hard to loosen the grip from once you submit to it!

We also have to ponder how many negative comments are actually bots trying to bring you down and draw you into this field that consequentially affects your quality of life!

I believe we recently found out that 50% of the comments on social media are bots. That leads me to believe that this is a planned weapon being used against others.

When you listen to this video you'll understand how taking part in their narrative is only a set up for our failure as God's children!

God is of love, comfort, and forgiveness. God is not of hate, fear, or division. Anyone sowing discord is either part of that plan to bring you down or is falling into the trap themselves!

"Sowing discord" means intentionally causing division, conflict, distrust, or strife among a group of people, ...

Between 1758 and 1875, the Comanche Nation killed an estimated 20,000 to 30,000 settlers, traders, and soldiers across Texas, New Mexico, Kansas, Oklahoma, and northern Mexico—more than any other Native American tribe during the westward expansion period. Their dominance stemmed from extraordinary horsemanship, developed after they acquired Spanish horses in the 1680s, transforming them into the most formidable mounted warriors in North American history. By the 1830s, the Comanche controlled approximately 240,000 square miles of territory—an area larger than modern New England—and had built what historians call the "Comanche Empire."

The Comanche waged systematic resistance against Spanish, Mexican, Texan, and American expansion for over a century. Their raiding strategy targeted isolated settlements, wagon trains, and ranches, often taking captives for ransom or adoption. Major conflicts included the Council House Fight of 1840, where negotiations turned into a bloodbath killing 35 ...

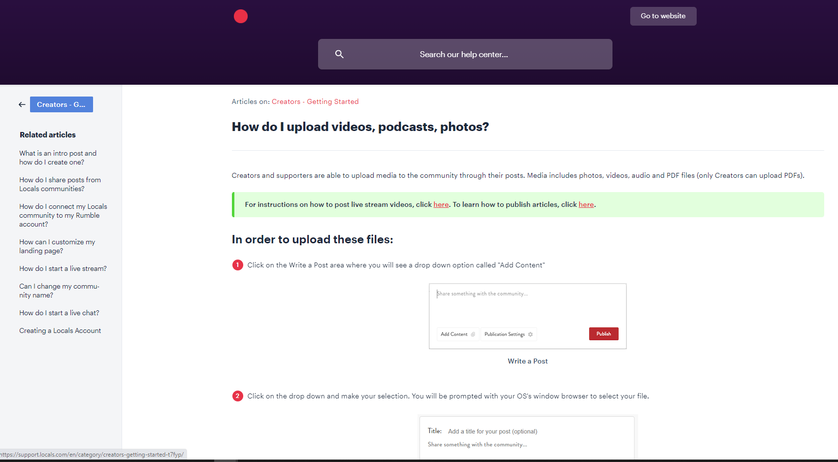

How to Use Locals Frequently Asked Questions and Help Topics:

https://support.locals.com/en/article/how-do-i-upload-videos-podcasts-photos-r49es4/

If you need more help contact LOCALS Support at: